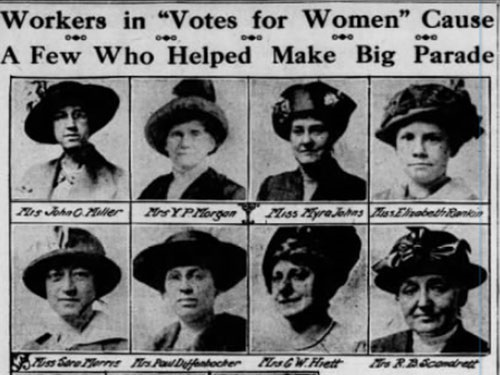

Pittsburgh Post, May 2, 1914.

Often excluded from suffrage events in other cities, African American suffragists participated with their white counterparts in, at least, some Pittsburgh activities. Of particular note is the Suffrage Parade, held on May 2, 1914, and led by Jeannie Bradley Roessing, Julian Kennedy, and Mary Bakewell. As published in many of the City’s newspapers of the time, the Suffrage Parade line up was integrated.

The 1914 Pittsburgh Suffrage Parade line up & Pittsburgh Daily Post, May 3, 1914.

The event included notable Caucasian women, African American women, and men. According to the Pittsburgh Daily Post, May 3, 1914, on parade day: “Race, creed and social standing were eliminated in the common cause”.

Chatham University students participating in an event 1907.

The parade began in downtown Pittsburgh, proceeded to Schenley Park, and returned downtown to conclude at the Jenkins Arcade.

Pittsburgh members of the National Association of Colored Women, in Pittsburgh’s 1914 Suffrage Parade.

Following the ‘notable women’ were 10 girls dressed in white with yellow sashes, representing the nation’s sole 10 states that had already passed suffrage.

Representing their local organizations, as well as the National Association of Colored Women, many of Pittsburgh’s prominent African American women filled the center of the parade.

Pittsburgh media devoted significant coverage to the suffrage parade. Pittsburgh Post, May 2, 1914.

Several men, including some City Councilmembers, also marched in the parade, underscoring that the fight to earn the vote needed to be a collective effort. Pittsburgh’s newspapers took note and regularly reported on suffragists’ activities.

Pittsburgh’s 1914 Suffrage Parade, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 3, 1914

The parade line up included students from the Pennsylvania College for Women, now Chatham University; mounted policemen, festive marching bands, Boy Scouts; a motorcade brought up the rear of the parade.

Mary Flinn Lawrence

Among the Pittsburgh women who organized and participated in suffrage rallies and marches, Mary Flinn Lawrence was a central figure. She was a well educated and wealthy who devoted herself to securing the vote for women. Thanks to Mary’s generous funding and her donating her time and use of a fleet of automobiles to the suffrage movement.

Adeline Levy Spear

MIGHTY WITTY

Adeline Levy Speer a member of Pittsburgh’s Jewish community, joined the ranks of our City’s witty and intrepid suffragists. While Adeline was active on the public side of the Votes for Women campaign, her sense of humor brought her acclaim. She created a memorable drink that she named “Suffrageade”.

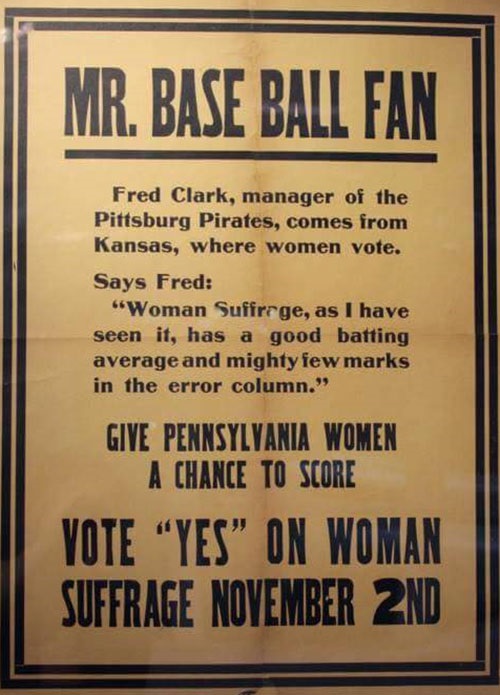

Fred Clark, the Pirates’ manager, was a somewhat unexpected ally for the suffragists.

Suffrage & the World Series

Suffragists nimbly jumped when opportunity presented itself. In the early 1900s, Pittsburgh newspapers received baseball scores directly from World Series games and would immediately write them up on large sheets of paper and display them in their windows to keep fans updated.

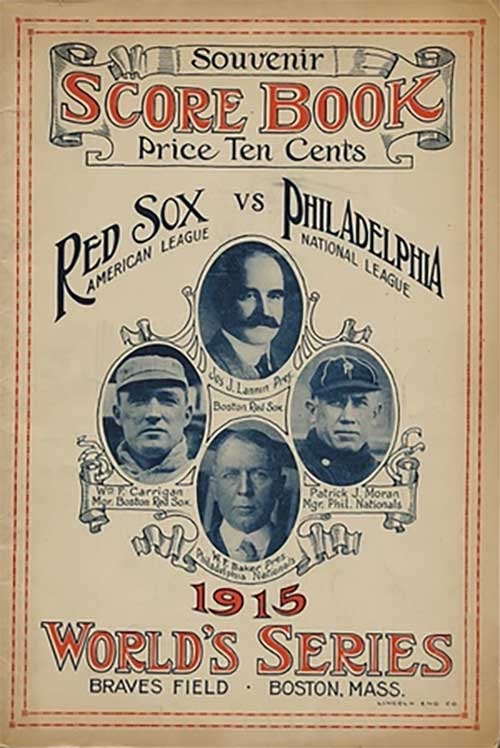

During the 1915 World Series, the sidewalks in front of newspaper offices became so congested with people waiting for score updates that Pittsburgh City Council banned window posters.

Eliza & Lucy Kennedy

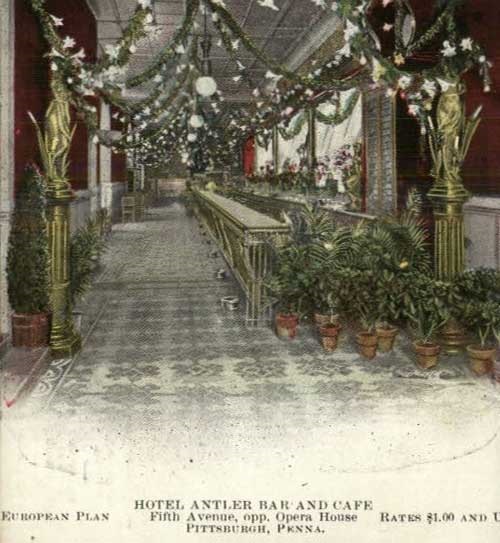

The ingenious Kennedy sisters, Lucy and Eliza, pounced on this opportunity. They convinced the owner of Antler Hotel to give suffragists a spot in the arcade to call out the latest scores.

Antler Hotel

During the breaks between score updates, the women spoke to the huge crowds about the need for equal voting rights.

Philadelphia and Red Sox teams, at the 1915 World Series.

Thousands of fans flowed in and out of the arcade to hear score updates, and the suffragists happily promoted that women voting led the way to the future.

Officers of the Women's League; Newport, RI

Echo Meetings

With so much happening on the suffrage front across the nation, keeping the news flowing was a constant challenge. Communications technology was limited as were the financial resources required for travel. Pittsburgh’s African American suffragists got the word out with Echo meetings. These gatherings involved one suffragist travelling to the distant gathering and reporting on it at several events in Pittsburgh.

Pittsburgh Press, July 11, 1915 article about the Writts garden party/fundraiser

Seeking Dollars for Suffrage

Raising the money necessary for suffrage organizing and materials was an on-going challenge that Pittsburgh’s suffragists met with attention getting happenings. From the Echo meetings, word would spread about the progress in the suffrage movement to those at Pittsburgh gatherings, including the frequent fund raising parties.

Pittsburgh Press, July 11, 1915 article about the Writts garden party/fundraiser

The Shirtwaist Ball

Winnifred Meek Morris spearheaded the Equal Franchise Association’s inventive Shirtwaist Ball; the shirtwaist was a popular type of blouse at the time.

Shirtwaists

The gala Shirtwaist Ball successfully met its goal by bringing together people from all classes to compete and create the best shirtwaist.

Shirtwaists Flier & Ethel Mary Ernst

The evening was full of dancing, performances, and finally, the competition. Suffragists used the event as a fund raiser funds and an opportunity to distribute information about their cause.

Poster advertising the Shirtwaist Ball. Heinz History Center.

The Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association raised over $2,500, the equivalent to $60,000 today, from the Shirtwaist Ball.

A stop along the Justice Bell’s tour of every PA county in support of the vote for women.

Justice Bell

Please click here to learn more about the remarkable, two-ton Justice Bell’s 1915 journey to every county in PA, masterminded by Pittsburgh’s Jennie Roessing.

Suffrage supporters outside the Allegheny Courthouse, downtown Pittsburgh circa 1915.

It’s plain to see that Pittsburgh’s Suffrage Squad overflowed with creativity, gumption and brains. Keep in mind that this website doesn’t cover the whole story. There were many additional suffragists who helped to push the movement forward.